Original Article |

Integration of artificial intelligence and traditional methods for ergonomic risk assessment

Integración de la inteligencia artificial y métodos clásicos para la evaluación de riesgos ergonómicos

Felipe,

Larez1 ![]()

![]() ; Yéssika, Maribao2

; Yéssika, Maribao2 ![]()

(1) Carlisle Construction Materials, Carlisle, EE UU.

(2) Anglo Latin Culture Research Center, Florida, EE UU.

Abstract

The evaluation of ergonomic risks has traditionally relied on classical methods involving direct observation, manual measurement, and postural categorization. These approaches are susceptible to variations based on the evaluator's experience and criteria. The adoption of artificial intelligence (AI), through computer vision, inertial sensors, and motion capture systems, offers a tool capable of enhancing accuracy, consistency, and real-time continuous monitoring. This study examines the benefits and drawbacks of both methods in assessing Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs), proposing a hybrid model that combines AI with validated techniques like REBA, RULA, and NIOSH, ensuring scientific rigor and practical relevance in actual work settings. From a regulatory standpoint, the global context and the latest U.S. legal framework are reviewed. The European Union leads with Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, which sets binding requirements for high-risk systems, including human oversight, traceability, and data protection. In Asia, ASEAN and Singapore are progressing through ethical guidelines and non-binding national strategies aimed at responsible AI governance. In the U.S., the October 2023 Executive Order was revoked on January 20, 2025, and replaced by Executive Order 14179 – Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence, emphasizing innovation and instructing federal agencies to review existing regulations. However, there is currently no comprehensive federal AI law. The order warns that unregulated use of automated tools, without professional validation, can pose legal and technical risks to workers and employers. In conclusion, a hybrid approach remains the most efficient, scientifically sound, and legally justifiable option, as it couples the speed of AI with professional oversight, methodological traceability, and adherence to international standards.

Keywords: Artificial Intelligence, Applied Ergonomics, Ergonomic Risks, Classical Methods, Legal Framework.

Resumen

La evaluación de riesgos ergonómicos ha dependido históricamente de métodos clásicos basados en observación directa, medición manual y categorización postural, lo que expone los resultados a variaciones derivadas de la experiencia y criterio del evaluador. La incorporación de inteligencia artificial (IA), mediante visión computacional, sensores inerciales y sistemas de captura de movimiento, introduce una herramienta capaz de incrementar la precisión, la consistencia y el monitoreo continuo en tiempo real. El presente estudio analiza las ventajas y limitaciones de ambos enfoques en la evaluación de Trastornos Musculoesqueléticos (TME), proponiendo un modelo híbrido que integra IA con métodos validados como REBA, RULA y NIOSH, garantizando rigor científico y aplicabilidad en entornos laborales reales. Desde la perspectiva normativa, se examina el contexto internacional y el marco legal estadounidense actualizado. La Unión Europea lidera con el Reglamento (UE) 2024/1689, que establece obligaciones vinculantes para sistemas de alto riesgo, incluyendo supervisión humana, trazabilidad y protección de datos. En Asia, la ASEAN y Singapur avanzan mediante guías éticas y estrategias nacionales sin carácter obligatorio, orientadas a la gobernanza responsable de la IA. En Estados Unidos, la Orden Ejecutiva de octubre de 2023 fue revocada el 20 de enero de 2025 y sustituida por la Executive Order 14179 – Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence, la cual prioriza la innovación e instruye a las agencias federales a revisar regulaciones previas, aunque aún no existe una ley federal general de IA. Se advierte que el uso no regulado de herramientas automatizadas, sin validación profesional, puede generar riesgos legales y técnicos para trabajadores y empleadores. En conclusión, el enfoque híbrido constituye la alternativa más eficiente, científicamente robusta y jurídicamente defendible, al conjugar la rapidez de la IA con la supervisión profesional, la trazabilidad metodológica y el cumplimiento de estándares internacionales.

Palabras clave: Inteligencia Artificial, Ergonomía Aplicada, Riesgos Ergonómicos, Métodos Clásicos, Marco Legal.

|

Recibido/Received |

21-08-2025 |

Aprobado/Approved |

29-10-2025 |

Publicado/Published |

30-10-2025 |

Introduction

Ergonomics has become an applied science focused on optimizing the interaction between people and the systems they use, applying principles, theories, and methods to design work environments that enhance both human well-being and organizational performance (Bazaluk et al., 2023). In this context, identifying and managing occupational risks becomes essential, especially regarding Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs), which are now considered one of the major challenges in occupational health. These conditions, affecting muscles, tendons, joints, bones, and nerves (Nygaard et al., 2022), significantly impact workers' quality of life and impose substantial economic costs on health systems and global productivity (Hulshof et al., 2021).

Exposure to ergonomic risk factors has become the leading cause of MSDs, with evidence consistently pointing to load handling, held postures, repetitive motions, and vibrations as the main triggers (Fan et al., 2022; Paskarini et al., 2025). These risks appear across multiple sectors, from healthcare – where nurses and physiotherapists face intense physical demands (Ayvaz et al., 2023; Pejčić et al., 2021)—to manufacturing, agriculture, and even highly specialized fields like surgery, where long procedures and static postures lead to significant injuries (Aaron et al., 2021; Monfared et al., 2022). In this context, rigorous ergonomic evaluation is not just a technical suggestion but an ethical and operational necessity.

Historically, ergonomics has relied on standardized methods that have demonstrated their validity over decades (Holzgreve et al., 2022). Tools like the NIOSH Revised Equation (1991), RULA, and REBA have been adopted by international organizations such as OSHA, NIOSH, ISO, and INSST, ensuring their scientific and legal legitimacy. However, these methods face clear limitations in modern work environments, which are characterized by their dynamic and variable nature. They require direct observation, manual measurements, and depend on the evaluator's judgment, which can introduce subjectivity and ambiguity (Pejčić et al., 2021). Additionally, by focusing only on specific moments of risk, they may overlook postural variability and accumulated fatigue (Raghavan et al., 2022). Their extensive application is also time-consuming, which restricts the ability to evaluate multiple jobs.

In response to these restrictions, the last decade has seen a significant transformation with the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into ergonomic assessment (Camargo Salinas et al., 2024). Advances in machine learning algorithms, computer vision, and wearable sensors have enabled the automation of observation, measurement, and risk analysis processes. Tools like OpenPose, DeepLabCut, and MediaPipe facilitate real-time biomechanical analysis by tracking key body points, allowing for continuous and objective measurements without human involvement (Chatzis et al., 2022; Scataglini et al., 2025). This ongoing monitoring helps identify movement and load patterns that might go unnoticed by humans (Yunus et al., 2021). Wearable devices complement this data with physiological information such as heart rate and acceleration, supporting predictive analytics related to fatigue and MSD risk. Results are compiled into detailed reports featuring heat maps, 3D simulations, and multifactorial analyses that help reduce human error (Chatzis et al., 2022). This technology has already proven effective in high-risk environments, such as robotic surgery, where ergonomic risks have been lowered compared to traditional laparoscopic procedures (Dixon et al., 2024; Monfared et al., 2022; Aaron et al., 2021).

However, the use of AI in professional ergonomics faces notable challenges. In the United States, the biggest issue is the lack of legal standardization: AI-based methods are not yet officially recognized by agencies like OSHA or NIOSH, which limits their regulatory acceptance. Additionally, the initial implementation cost—estimated at $500 per month—and the requirement for specialized technical training make it hard for small and medium-sized companies to adopt. Continuous monitoring in the workplace also raises privacy concerns. From a technical perspective, AI often provides corrective suggestions that are too generic and fail to adequately address complex risks such as mental load, an aging workforce, or gender differences (Nygaard et al., 2022). Consequently, there is a risk that the ease of use of these tools will overshadow expert judgment, undermining the comprehensive approach that ergonomics demands.

This dilemma creates a core tension between the normative validation of traditional methods and AI's objective efficiency. The task is to balance technological accuracy with scientific rigor without losing professional judgment (Danylak et al., 2024). This article aims to resolve this tension through a comparative analysis and the development of an integrated approach that assesses the benefits and limitations of both methods in the quantitative evaluation of ergonomic risks.

Regarding the regulatory framework, the use of AI in workplaces has progressed unevenly. The European Union has led with Regulation 2024/1689, which sets binding rules for high-risk AI systems, including human oversight, algorithmic transparency, traceability, and data protection (European Commission, 2024). In Asia, the approach is more focused on ethics and technical standards. In 2024, ASEAN issued a guide for AI governance based on principles like fairness, safety, and human control, though it lacks binding legal authority (ASEAN, 2024). Singapore also enhanced its national AI strategy in 2023, incorporating technical protocols and sector-specific guidelines for workplaces such as automated posture assessment tools used in occupational health and manufacturing (Smart Nation Singapore, 2023).

In the United States, the landscape changed in 2025. The October 2023 Executive Order, which proposed safety and oversight guidelines for the use of AI, was revoked on January 20, 2025, and replaced by Executive Order 14179 – Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence, signed on January 23, 2025. This order reorients federal policy toward innovation and technology infrastructure (The White House, 2025). Although it establishes guidelines of federal scope, the United States does not yet have a federal law regulating AI application. In occupational health and safety, no specific technical standards have been issued to regulate AI in ergonomic assessments. Both OSHA and NIOSH recognize the potential of these technologies and have published guidance on automation, robotics, and workplace innovation; however, these materials are research-based or best practices and are not mandatory. As a result, in the absence of binding federal standards, AI can only serve as a supplementary tool, and its technical legitimacy depends on professional oversight, methodological traceability, and the use of validated ergonomic methods such as REBA, RULA, and NIOSH.

Materials and methods

Classical ergonomics and standardized methods

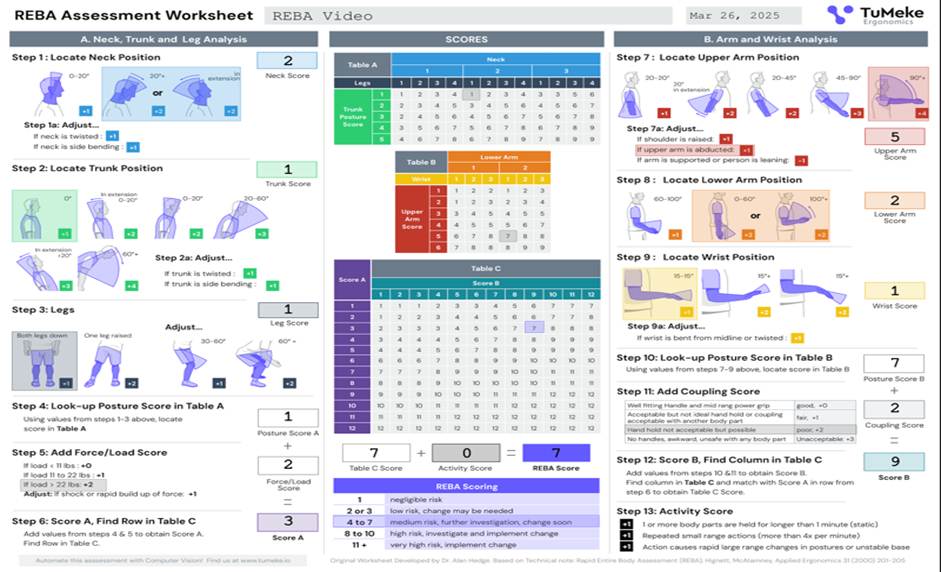

Classical methods involve direct observation or manual measurement of factors such as postures, angles, frequencies, weight, and duration, with results depending on the evaluator's criteria and the visual or written record. These methods are standardized and widely accepted by OSHA, NIOSH, ISO, and INSST. Examples of classic methods include the NIOSH Revised Equation (1991), RULA, REBA, Moore & Garg's Strain Index, MAPO, DINO (hospital sector), ISO 11228, and ISO 12296. Figure 1 shows an example of the typical template used for applying the EBR Method.

Figure 1. Classic REBA method template

Assessments Using Artificial Intelligence

AI assessments are conducted through:

· Computer vision video analysis: Using tools like OpenPose, DeepLabCut, or MediaPipe.

· Wearable sensors: Equipped with AI to measure physiological and biomechanical variables like heart rate, acceleration, posture, and fatigue.

· Machine learning algorithms: They predict the risk of MSDs using large databases.

2.3 Proposed Hybrid Approach

It is proposed to perform ergonomic risk assessments using a hybrid approach. This model combines AI with traditional methods, aiming for AI + Classical method = accuracy + scientific validation. The suggested process is:

1. Recording of the worker using a camera or AI sensor (capturing posture, angles, load).

2. The software automatically identifies the position of the trunk and limbs.

3. The biomechanical data is exported, and a standard method (e.g., RULA or REBA) is automatically applied.

4. The ergonomist confirms the final result through visual observation, noting the contributing factors.

Results

This section highlights the contributions of traditional ergonomic assessment methods (RULA, REBA, and NIOSH) in the sample of jobs analyzed. This data will serve as a basis for comparing the accuracy, runtime, and objectivity of AI in the next section.

Contributions of postural risk using the RULA and REBA methods

The evaluation of workers' postures during critical tasks is provided. The final RULA and REBA scores are included to assess the level of risk and determine if immediate corrective actions are necessary. Table 1 summarizes these findings.

Table 1. Contributions of the postural assessment of ergonomic risk (RULA and REBA)

|

Job Position |

Task Analyzed |

RULA Final Score |

RULA Action Level (1-4) |

REBA Final Score |

REBA Action Level (1-5) |

Intervention Priority (High/Medium/Low) |

|

Assembly Operator (Line A) |

Placement of top parts |

6 |

3 (Prompt Action Needed) |

9 |

3 (High Risk) |

Loud |

|

Quality Inspector (Station 4) |

Visual Component Review |

3 |

1 (Acceptable Risk) |

4 |

1 (Negligible Risk) |

Casualty |

|

Warehouse Operator (Picking) |

Lifting medium-sized boxes |

7 |

4 (Immediate Action Required) |

12 |

4 (Very High Risk) |

Loud |

|

Office Assistant (Typing) |

Keyboard and mouse functioning |

4 |

2 (Research) |

6 |

2 (Medium Risk) |

Stocking |

|

(... Other positions in the sample) |

||||||

Table 1 shows how classic ergonomic evaluation methods are applied to analyze working postures. Both the REBA (Rapid Entire Body Assessment) and the RULA (Rapid Upper Limb Assessment) methods enable the evaluator, through systematic observation of tasks, to determine the level of ergonomic risk the worker faces.

During the evaluation process, joint angles, loads, and forces applied to different body segments, such as the neck, shoulders, back, wrists, and lower extremities, are identified and recorded. Based on these parameters, the level of risk and the actions necessary for its management are determined.

For example, in the roles of Office Assistant and Quality Inspector, the identified risks can be reduced through the use of administrative measures. Conversely, when risk levels are high, as with Assembly Operator and Warehouse Operator positions, implementing engineering measures is advised, as these are more effective at lowering and controlling ergonomic risk factors.

Manual handling risk assessment (NIOSH)

The results from the NIOSH Revised Equation (1991) for load lifting tasks are shown. The analysis emphasizes the Recommended Weight Limit (LPR) compared to the weight lifted and the calculation of the Lift Index (IL), which reflects the risk level. Table 2 displays the findings.

Table 2. Load lifting evaluation contributions (NIOSH Equation)

|

Lifting Task |

Weight Lifted (Kg) |

Reduction Factors (RF) |

Recommended Weight Limit (LPR) |

Lift Index (IL) |

Risk Conclusion (IL ≥ 1) |

|

Warehouse Operator (Picking) |

18 |

FR = 0.65 |

11.3 kg |

1,59 |

High Risk |

|

Line Operator (Stacked) |

10 |

FR = 0.80 |

14.7 Kg |

0,68 |

Acceptable Risk |

|

Truck Loader |

25 |

FR = 0.45 |

8.8 Kg |

2,84 |

Critical Risk |

Table 2 shows the application of another standard ergonomic assessment method, the NIOSH Lifting Equation, used for the quantitative evaluation of the risk related to manual load handling tasks. In this example, three jobs with different physical effort parameters were assessed.

The NIOSH method requires accurately measuring variables such as the horizontal (H) and vertical (V) coordinates of the load, the travel distance (D), the lifting frequency (F), the task duration (t), and the quality of the grip (C) between the hands and the object being handled. Using these factors, the Lifting Index (LI) is calculated, which helps assess the ergonomic risk level and determine the needed corrective actions.

In this context, risk control can be initiated through administrative measures, such as reducing the frequency of surveys or redistributing tasks to lower individual exposure. However, when these measures fail to bring the risk to acceptable levels, implementing engineering measures that modify the physical workplace conditions and effectively minimize ergonomic risks associated with lifting loads becomes necessary.

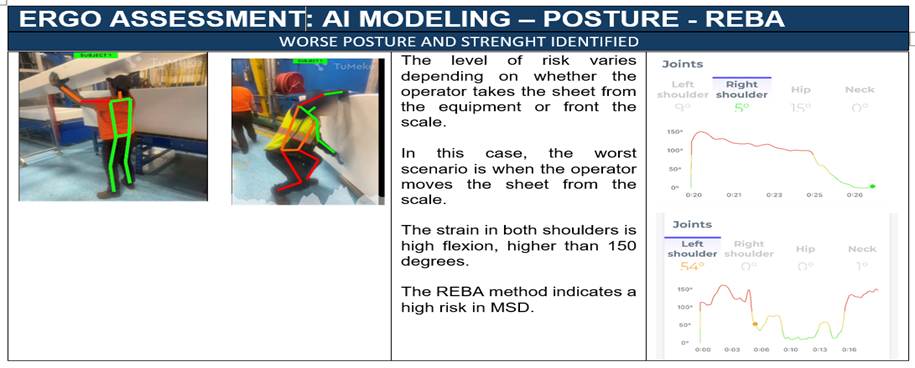

Contributions of AI in real-time biomechanical analysis

Figure 2, demonstrates the AI's ability to perform real-time biomechanical analysis, showing how stresses in different body segments are visualized. This offers a clear advantage over traditional manual angle recording methods.

Figure 2. They display the forces related to various body segments using AI

Automation and "Time Saving" are important elements since the analyses reduce the analysis time from hours to minutes; the "Continuous Monitoring" allows the worker to be evaluated throughout the day, reducing the exposure time for data collection."Objectivity and consistency” enable algorithms to apply the same criteria to all evaluations, "Reducing Subjectivity and Ambiguity"; these algorithms also have "Predictive Capacity" in identifying risk patterns before injuries and MSDs occur (Table 3).

AI in ergonomics enables an "Advanced Multi-Factor Visualization" by creating heat maps, 3D reports, and biomechanical simulations that incorporate multiple variables: posture, heart rate, speed, fatigue, and thermal stress.

Table 3. Functionalities of artificial intelligence for real-time biomechanical analysis

|

key aspect |

ai system capability |

ergonomic benefit |

|

Data Collection and Measurement |

Video analysis with computer vision (OpenPose, DeepLabCut, MediaPipe) or wearable sensors. |

It enables precise measurement of angles, posture, and acceleration without depending on manual measurement. |

|

Time Efficiency |

It automates observation, measurement, and calculation processes. |

Analysis time drops from hours to minutes. |

|

Monitoring and Consistency |

It enables ongoing monitoring and the use of consistent criteria by algorithms. |

It minimizes the subjectivity and ambiguity of the results and monitors the worker throughout the day. |

|

Pattern Detection |

It detects patterns of movement, force, or charge that might go unnoticed by humans eye. |

It enhances the precision and thoroughness of risk diagnosis. |

|

Advanced Analytics |

Creates advanced multi-factor visualizations (heat maps, 3D reports, biomechanical simulations). |

It enables the integration of multiple variables in real time: posture, heart rate, speed, fatigue, and thermal stress. |

|

Predictive Capability |

Machine learning algorithms forecast the risk of MSDs. |

It enables the detection of risk patterns before injuries and MSDs occur. |

Applied ergonomics: hybrid approach

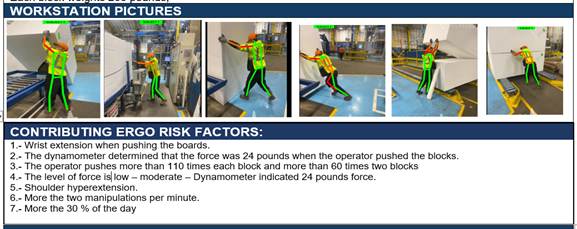

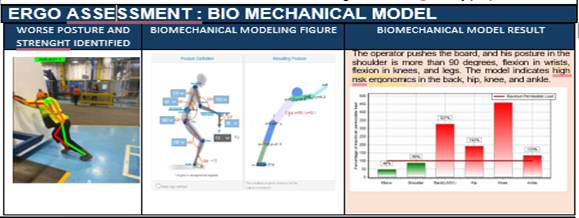

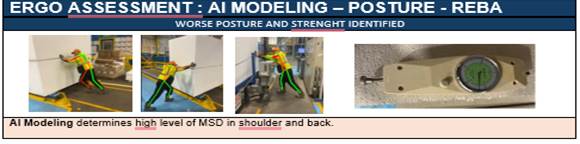

The practical and visual validation of a hybrid ergonomic assessment approach, which combines AI with traditional ergonomic methods and physical measurements. Figure 3 (a, b, and c) demonstrates this integrated methodology, illustrating how the technology is supported and supervised by expert judgment.

Figure 3 shows that AI handles the capture and initial processing by modeling the worker's posture in real time and automatically identifying efforts and the worst postures in joints such as shoulders, elbows, wrists, back, and legs. This technology-assisted analysis is complemented by an ergonomist's validation, who reviews the data, lists specific contributing factors (such as wrist extension or shoulder hyperextension), and ensures the process aligns with the prevention of Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs).

Furthermore, the hybrid approach combines physical measurement tools and advanced modeling, such as two-dimensional biomechanical analysis and using a dynamometer to measure actual force applied (e.g., 24 pounds). This data validation enables a quantitative analysis, where the biomechanical model produces graphical results that compare joint demands (e.g., back, knee) with the Maximum Permissible Load, confirming the presence of significant ergonomic risks across multiple body segments due to extreme postures and frequent manipulation. In summary, the figures illustrate the synergy between AI automation and the professional's contextual and detailed interpretation.

Another important aspect to consider is the corrective actions generated by artificial intelligence models, which are usually generic, simple, and not very specific. In this context, it is recommended that ergonomics professionals use this tool as a support to reduce analysis times and enhance the accuracy of results.

Discussion

The results of this research reveal a deep duality in the landscape of ergonomic risk assessment: on one side, the regulatory strength and historical validation of traditional methods; on the other, the unmatched efficiency and objectivity provided by Artificial Intelligence (AI). The discussion centers on contrasting these two approaches, examining AI's key limitations and emphasizing the ongoing need for a Hybrid Approach where the professional ergonomist remains the validator and strategist.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. a) Worker efforts with artificial intelligence, focusing on shoulders, elbows, and wrists; meanwhile, the ergonomist confirms by listing factors that may cause a TME. b) Ergonomics analysis using a hybrid approach; with AI, efforts are monitored in real time in the legs, back, shoulders, and elbows; by combining these results, we can determine the applied force with a two-dimensional biomechanical model and a dynamometer as measuring tools. c) The ergonomist confirms the results by listing factors that can cause a TME (e.g., wrist extension, force measured by dynamometer, shoulder hyperextension, and manipulation frequency), while AI observes body efforts.

The use of traditional methods like the Revised Equation of NIOSH (1991), RULA, and REBA (Holzgreve et al., 2022) confirmed significant risks within the sample of jobs, aligning with literature on MSD morbidity across various sectors (Ayvaz et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2022). These tools provide a crucial baseline for risk management (Bazaluk et al., 2023), and their application is essential to meet international standards set by organizations such as OSHA, NIOSH, and ISO (Hulshof et al., 2021). However, the operational results show that the primary limitation of these methods is their reliance on direct observation and manual measurement (postures, angles, frequencies, weight, duration), which is time-consuming and vulnerable to evaluator subjectivity and ambiguity. The intermittent observation method—capturing only the "worst moment"—cannot account for postural variability or fatigue buildup over a shift, a concern previously noted in the literature (Pejčić et al., 2021; Raghavan et al., 2022). Unlike AI's ability to monitor continuously, manual techniques fall short in accurately assessing true risk exposure over longer periods.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence into ergonomic evaluation directly addresses the operational weaknesses of the traditional approach. The findings confirm that AI, through computer vision (OpenPose, MediaPipe) and wearables, enables the automation of observation, measurement, and calculation processes (Camargo Salinas et al., 2024), resulting in significant time savings by reducing analyses from hours to minutes. The most notable benefit of AI is its ability for real-time biomechanical analysis, offering objectivity and consistency that manual measurement cannot achieve (Chatzis et al., 2022; Scataglini et al., 2025). AI not only measures angles but also identifies movement and force patterns and integrates multiple variables (posture, heart rate, speed) through Advanced Multi-Factor Visualization (Yunus et al., 2021). This continuous monitoring capability and the consistent application of algorithmic criteria across all assessments minimize human error and ambiguity often found in written records (Chatzis et al., 2022). Such accuracy is especially valuable in highly complex environments, as shown by studies using kinematic analysis to assess ergonomic risk in surgical procedures. For example, comparisons between traditional laparoscopic surgery and robotic-assisted surgery reveal that the latter significantly reduces ergonomic risk for the surgeon by optimizing static postures (Aaron et al., 2021; Dixon et al., 2024; Monfared et al., 2022). These findings reaffirm AI as not only a measurement tool but also as an enabler of engineering risk control solutions, providing predictive data that surpasses the simple risk classification (scoring) typical of REBA and RULA.

Despite its significant benefits, the review of results and literature highlights key barriers that prevent AI from fully replacing the human ergonomist, with the most pressing being the absence of legal standardization. Although AI is accurate, it is not officially recognized by organizations like OSHA or NIOSH as a primary evaluation method. As a result, its outcomes, despite being superior in raw data, lack the legal authority needed for regulatory compliance. This restricts their current role to supporting functions rather than serving as a replacement. Besides deployment challenges such as the high initial cost of hardware and software (up to $500 per month) and the necessity for specialized technical training to configure and calibrate models, which hinder widespread adoption (Camargo Salinas et al., 2024), ethical concerns related to data privacy—due to continuous video recordings—must also be addressed through strict anonymization protocols.

This limitation becomes even clearer when examining the legal framework for AI in ergonomics. The European Union has set mandatory requirements through Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, which labels these applications as high-risk and mandates human oversight, traceability, and data protection. In Asia, ASEAN and Singapore are developing ethical guidelines and national strategies for responsible governance, though these lack binding legal force. In the United States, the October 2023 Executive Order was revoked and replaced by Executive Order 14179 (01/23/2025), emphasizing innovation and leaving regulatory details to federal agencies. Still, the absence of a nationwide law results in a scattered framework, making AI use in ergonomics rely on its supportive role, human supervision, and adherence to validated methods.

This overview raises the question of whether general AI legislation is enough to regulate its use in ergonomics. Evidence shows it is not because AI assessments involve biometric data collection, automated movement analysis, and issuing recommendations that can influence work decisions. These aspects require specific guidelines on informed consent, scientific validation of algorithms, compatibility with traditional methods (REBA, RULA, NIOSH), and professional oversight by certified ergonomists. Without clear protocols, legal risks such as unvalidated automated assessments, misuse of recordings, or algorithmic errors that underestimate actual risks may arise for employers and workers. Currently, agencies like OSHA and NIOSH allow AI as a supplementary tool but insist that assessments rely on validated ergonomic methods. Therefore, creating technical guides to incorporate AI support, establish interoperability standards, and define consent and data protection protocols is recommended.

The deeper challenge, however, is the analytical limitation of AI. While the technology is effective for measuring biomechanical variables (angles, forces, frequencies), current models are inadequate for addressing complex, non-biomechanical ergonomic risk factors. These include mental load, risks related to an aging workforce (aging workforce, Nygaard et al., 2022), gender ergonomics, and the interaction of psychosocial and lifestyle factors that influence MSDs (Paskarini et al., 2025). Additionally, it was observed that the corrective actions suggested by AI models are often "very generic, simple, and vague." The machine can identify when a worker's posture is high-risk but lacks the cognitive ability to specify contributing factors and recommend detailed engineering, administrative controls, or process design solutions.

The solution to this dilemma is not substitution but integration or the Hybrid Approach to assessment. This core idea is based on the fact that AI and the human ergonomist play complementary and irreplaceable roles. AI should be used to leverage its operational strengths: reducing analysis time through continuous monitoring and objective measurement of posture and effort (speed and accuracy). By exporting this objective data (angles, frequencies) from the AI to a spreadsheet, the standardized formula of a traditional method (RULA, REBA, NIOSH) can be applied, ensuring scientific and legal validation of the results (Danylak et al., 2024). The expert ergonomist regains their central role by performing the final validation through human observation, applying their criteria to: 1) confirm that the automated data reflect reality, 2) incorporate non-biomechanical risk factors (mental load, thermal environment, psychosocial) that AI overlooks, and 3) translate the machine-generated risk score into specific corrective actions that are thorough and effective, addressing the root causes rather than just the postural symptoms.

The formula AI + Classical Method = precision + scientific validation stands as the strongest proposal for the future. It enables faster and more accurate ergonomic assessments through technology, while still maintaining analytical rigor and international acceptance through human judgment and standardized methods (Bazaluk et al., 2023). This hybrid approach not only improves human well-being and the performance of the production system but also places the professional ergonomist at the forefront of technological advancement. In this context, the hybrid approach—combining AI with validated classical methods such as REBA, RULA, and NIOSH—is not only technically effective but also the safest and most legally defensible option.

Finally, it is important to emphasize that the employer, as the legal entity responsible for working conditions, also needs regulatory protections. The employer hires the ergonomics professional, follows the recommendations from studies, and is accountable to workers and federal agencies (such as OSHA and NIOSH) if there is noncompliance or negligence. Therefore, regulation should include clear protocols for shared responsibility between the ergonomist and the employer, technical standards that support the use of AI as a supplementary tool, and compliance guidelines that enable the employer to demonstrate due diligence in assessing ergonomic risks. Well-balanced regulation not only safeguards workers from potential technological misuse but also protects the employer from unwarranted labor lawsuits or errors caused by unverified automated systems. In essence, a regulatory framework for AI ergonomics is not just a technical requirement but an ethical and legal duty to create safe, transparent, and fair work environments.

Final considerations

The use of artificial intelligence marks a significant step forward in the quantitative evaluation of ergonomic risks, providing greater objectivity, consistency, and efficiency compared to traditional methods. However, AI still has limitations: lack of legal standards, high costs, technological dependence, and reduced ability to capture qualitative or contextual factors. Therefore, the literature and professional practice agree that the most effective approach is a hybrid one: AI as a tool for gathering and analyzing data, and the ergonomist as a technical expert capable of interpreting, validating, and translating those results into corrective actions. This collaboration ensures scientific rigor, international acceptance, and defensible results from both technical and legal perspectives.

At the regulatory level, the European Union implemented a binding framework through Regulation (EU) 2024/1689, which mandates transparency, traceability, and human oversight in high-risk systems. In Asia, ASEAN and Singapore have promoted ethical frameworks and national strategies that guide the responsible use of AI without binding legal force.

In the United States, federal policy shifted in 2025. The Executive Order issued in October 2023 was rescinded on January 20, 2025, and replaced by Executive Order 14179 – Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence, issued on January 23, 2025. This new framework emphasizes innovation and assigns federal agencies the task of reviewing and updating existing regulations. However, the country still lacks a comprehensive federal AI law that establishes minimum and uniform principles for the entire system. Without such standards, regulation remains fragmented across different agencies, which can result in gaps, inconsistencies, or varying standards.

From a comparative legal perspective, a federal framework law on AI would not mean legislating each specific application – such as ergonomics – but rather establishing guiding principles: security, algorithmic transparency, human oversight, data protection, professional responsibility, and traceability. Each federal agency, including OSHA, could then develop sector-specific technical standards under that common legal framework, which would provide coherence, institutional stability, and legal certainty for employers, workers, and technology developers.

In this context, the hybrid approach—AI plus validated classic methods like RULA, REBA, and NIOSH—remains the safest, most scientifically sound, and legally defensible option. It enables professional supervision to be maintained, ensures methodological traceability, and reduces subjectivity in analyses, providing solid technical defenses against audits or labor claims.

In short, while the United States makes progress in practice and innovation, the lack of a federal framework law limits regulatory consistency and leaves it to each agency to develop partial guidelines. Having a general legal framework would not restrict technology but ensure that AI used in work— including ergonomics— is developed according to universal ethical principles and basic labor rights. The technology is already ready; now it is up to the law to establish rules that enable safe, fair, and compatible use, while protecting the integrity and well-being of workers in the workplace.

Acknowledgments

To our collaborators.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

Aaron, K. A., Vaughan, J., Gupta, R., Ali, N. E., Beth, A. H., Moore, J. M., Ma, Y., Ahmad, I., Jackler, R. K., & Vaisbuch, Y. (2021). The risk of ergonomic injury across surgical specialties. PLoS One, 16(2), e0244868. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244868

ASEAN. (2024). ASEAN guide on AI governance and ethics. ASEAN Secretariat. https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/ASEAN-Guide-on-AI-Governance-and-Ethics_beautified_201223_v2.pdf

Ayvaz, Ö., Özyıldırım, B. A., İşsever, H., Öztan, G., Atak, M., & Özel, S. (2023). Ergonomic risk assessment of working postures of nurses working in a medical faculty hospital with REBA and RULA methods. Science Progress, 106(4), 368504231216540. https://doi.org/10.1177/00368504231216540

Bazaluk, O., Tsopa, V., Cheberiachko, S., Deryugin, O., Radchuk, D., Borovytskyi, O., & Lozynskyi, V. (2023). Ergonomic risk management process for safety and health at work. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1253141. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1253141

Camargo Salinas, M. A., Miranda Arandia, N. Y., & Suárez Pérez, J. F. (2024). Estado del arte en evaluación de métodos de detección automatizada de riesgo ergonómico en entornos de trabajo industrial. Gestión de la Seguridad y la Salud en el Trabajo, 6(2), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.15765/jzdrd646

Chatzis, T., Konstantinidis, D., & Dimitropoulos, K. (2022). Automatic ergonomic risk assessment using a variational deep network architecture. Sensors (Basel), 22(16), 6051. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22166051

Danylak, S., Walsh, L. J., & Zafar, S. (2024). Measuring ergonomic interventions and prevention programs for reducing musculoskeletal injury risk in the dental workforce: A systematic review. Journal of Dental Education, 88(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.13403

Dixon, F., Vitish-Sharma, P., Khanna, A., Keeler, B. D., & VOLCANO Trial Group. (2024). Robotic assisted surgery reduces ergonomic risk during minimally invasive colorectal resection: The VOLCANO randomised controlled trial. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery, 409(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03322-y

European Commission. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on artificial intelligence. Official Journal of the European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj

Fan, L. J., Liu, S., Jin, T., Gan, J. G., Wang, F. Y., Wang, H. T., & Lin, T. (2022). Ergonomic risk factors and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in clinical physiotherapy. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1083609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1083609

Holzgreve, F., Fraeulin, L., Betz, W., Erbe, C., Wanke, E. M., Brüggmann, D., Nienhaus, A., Groneberg, D. A., Maurer-Grubinger, C., & Ohlendorf, D. (2022). A RULA-based comparison of the ergonomic risk of typical working procedures for dentists and dental assistants. Sensors (Basel), 22(3), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22030805

Hulshof, C. T. J., Pega, F., Neupane, S., Colosio, C., Daams, J. G., Kc, P., Kuijer, P. P. F. M., Mandic-Rajcevic, S., Masci, F., van der Molen, H. F., Nygård, C. H., Oakman, J., Proper, K. I., & Frings-Dresen, M. H. W. (2021). The effect of occupational exposure to ergonomic risk factors on osteoarthritis of hip or knee and selected other musculoskeletal diseases. Environmental International, 150, 106349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.106349

Monfared, S., Athanasiadis, D. I., Umana, L., Hernandez, E., Asadi, H., Colgate, C. L., Yu, D., & Stefanidis, D. (2022). A comparison of laparoscopic and robotic ergonomic risk. Surgical Endoscopy, 36(11), 8397–8402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09105-0

Nygaard, N. B., Thomsen, G. F., Rasmussen, J., Skadhauge, L. R., & Gram, B. (2022). Ergonomic and individual risk factors for musculoskeletal pain in the ageing workforce. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1975. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14386-0

Paskarini, I., Dwiyanti, E., Mahmudah, M., Widarjanto, W., Nugroho, S. A., & Syaiful, D. A. (2025). The interplay of ergonomic risk factor and lifestyle factors on Potter's well-being and work fatigue in Magelang's tourism village. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22780-7

Pejčić, N., Petrović, V., Đurić-Jovičić, M., Medojević, N., & Nikodijević-Latinović, A. (2021). Analysis and prevention of ergonomic risk factors among dental students. European Journal of Dental Education, 25(3), 460–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12621

Raghavan, R., Panicker, V. V., & Emmatty, F. J. (2022). Ergonomic risk and physiological assessment of plogging activity. Work, 72(4), 1337–1348. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-205210

Scataglini, S., Fontinovo, E., Khafaga, N., Khan, M. U., Khan, M. F., & Truijen, S. (2025). A systematic review of the accuracy, validity, and reliability of markerless versus marker camera-based 3D motion capture for industrial ergonomic risk analysis. Sensors (Basel), 25(17), 5513. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25175513

Smart Nation and Digital Government Office. (2023). National AI Strategy 2.0. Government of Singapore. https://www.smartnation.gov.sg/initiatives/national-ai-strategy

The White House. (2025, January 23). Executive Order 14179 – Removing barriers to American leadership in artificial intelligence. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/31/2025-02172/removing-barriers-to-american-leadership-in-artificial-intelligence

Yunus, M. N. H., Jaafar, M. H., Mohamed, A. S. A., Azraai, N. Z., & Hossain, M. S. (2021). Implementation of kinetic and kinematic variables in ergonomic risk assessment using motion capture simulation: A review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168342